Townsend discharge

The Townsend discharge is a gas ionization process where an initially very small amount of free electrons, accelerated by a sufficiently strong electric field, give rise to electrical conduction through a gas by avalanche multiplication: when the number of free charges drops or the electric field weakens, the phenomena ceases. It is a process characterized by very low current densities: in common gas filled tubes, typical magnitude of currents flowing during this process range from about 10−18A to about 10−5A, while applied voltages are almost constant. Subsequent transition to ionisation processes of dark discharge, glow discharge, and finally to arc discharge are driven by increasing current densities: in all these discharge regimes, the basic mechanism of conduction is avalanche breakdown. Townsend discharge is named after John Sealy Townsend, and is also commonly known by practitioners as a "Townsend avalanche".

Contents |

Quantitative description of the phenomenon

The basic setup of the experiments investigating ionization discharges in gases consist of a planar parallel plate capacitor filled with a gas and a continuous current high voltage source connected between its terminals: the terminal at the lower voltage potential is named cathode while the other is named anode. Forcing the cathode to emit electrons (eg. by irradiating it with a X-ray source), Townsend found that the current  flowing into the capacitor depends on the electric field between the plates in such a way that gas ions seems to multiply as they moved between them. He observed currents varying over ten or more orders of magnitude while the applied voltage was virtually constant. The experimental data obtained from his experiments are described by the following formula

flowing into the capacitor depends on the electric field between the plates in such a way that gas ions seems to multiply as they moved between them. He observed currents varying over ten or more orders of magnitude while the applied voltage was virtually constant. The experimental data obtained from his experiments are described by the following formula

where

is the current flowing in the device,

is the current flowing in the device, is the photoelectric current generated at the cathode surface,

is the photoelectric current generated at the cathode surface, is the Euler number

is the Euler number is the first Townsend ionisation coefficient, expressing the number of ion pairs generated per unit length (e.g. meter) by a negative ion (anion) moving from cathode to anode,

is the first Townsend ionisation coefficient, expressing the number of ion pairs generated per unit length (e.g. meter) by a negative ion (anion) moving from cathode to anode, is the distance between the plates of the device.

is the distance between the plates of the device.

The almost constant voltage between the plates is equal to the breakdown voltage needed to create a self-sustaining avalanche: it decreases when the current reaches the glow discharge regime. Subsequent experiments revealed that the current  rises faster than predicted by the above formula as the distance

rises faster than predicted by the above formula as the distance  increases: two different effects were considered in order to explain the physics of the phenomenon and to be able to do a precise quantitative calculation.

increases: two different effects were considered in order to explain the physics of the phenomenon and to be able to do a precise quantitative calculation.

Gas ionisation caused by motion of positive ions

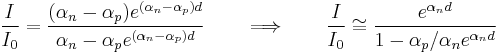

Townsend put forward the hypothesis that positive ions also produce ion pairs, introducing a coefficient  expressing the number of ion pairs generated per unit length by a positive ion (cation) moving from anode to cathode. The following formula was found

expressing the number of ion pairs generated per unit length by a positive ion (cation) moving from anode to cathode. The following formula was found

since  , in very good agreement with experiments.

, in very good agreement with experiments.

The first Townsend coefficient ( α ), also known as first Townsend avalanche coefficient is a term used where secondary ionization occurs because the primary ionization electrons gain sufficient energy from the accelerating electric field, or from the original ionizing particle. The coefficient gives the number of secondary electrons produced by primary electron per unit path length.

Cathode emission caused by impact of ions

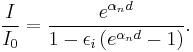

Townsend, Holst and Oosterhuis also put forward an alternative hypothesis, considering augmented emission of electrons by cathode caused by positive ions impact, introducing Townsends second ionization coefficient  , the average number of electrons released from a surface by an incident positive ion, and working out the following formula:

, the average number of electrons released from a surface by an incident positive ion, and working out the following formula:

These two formulas may be thought as describing limiting cases of the effective behavior of the process: note that they can be used to well describe the same experimental results. Other formulas describing, various intermediate behaviors, are found in the literature, particularly in reference 1 and citations therein.

Avalanche

A Townsend avalanche is a cascade reaction involving electrons in a region with a sufficiently high electric field. This reaction must also occur in a medium that can be ionized, such as air. The positive ion drifts towards the cathode, while the free electron drifts towards the anode of the particular device. It accelerates in the electric field, gaining sufficient energy such that it frees another electron upon collision with another atom/molecule of the medium. The two free electrons then travel together some distance before another collision occurs. The number of electrons travelling towards the anode is multiplied by a factor of two for each collision, so that after n collisions, there are 2n free electrons.

Conditions

A Townsend discharge can be sustained over a limited range of gas pressure and electric field intensity. At higher pressures, discharges occur more rapidly than the calculated time for ions to traverse the gap between electrodes, and the streamer theory of spark discharge is applicable. In highly non-uniform electric fields, the corona discharge process is applicable. Discharges in vacuum require vaporization and ionization of electrode atoms. An arc can be initiated without a preliminary Townsend discharge; for example when electrodes touch and are then separated.

Applications

- Avalanche multiplication during Townsend discharge is naturally used in gas phototubes, to amplify the photoelectric charge generated by incident radiation (visible light or not) on the cathode: achievable current is typically 10~20 times greater respect to that generated by vacuum phototubes.

- The starting of Townsend discharge sets the upper limit to the blocking voltage a glow discharge gas filled tube can withstand : this limit is the Townsend discharge breakdown voltage also called ignition voltage of the tube.

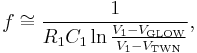

- The presence of Townsend discharge and glow discharge breakdown voltages shapes the

characteristic of any gas diode or neon lamp in a way such that it has a negative differential resistance region of the S-type. This occurrence is typically used to generate electrical oscillations and waveforms, as in the relaxation oscillator whose schematic is shown in the picture on the right. The sawtooth shaped oscillation generated has frequency

characteristic of any gas diode or neon lamp in a way such that it has a negative differential resistance region of the S-type. This occurrence is typically used to generate electrical oscillations and waveforms, as in the relaxation oscillator whose schematic is shown in the picture on the right. The sawtooth shaped oscillation generated has frequency

- where

is the glow discharge breakdown voltage,

is the glow discharge breakdown voltage, is the Townsend discharge breakdown voltage,

is the Townsend discharge breakdown voltage, ,

,  and

and  are respectively the capacitance, the resistance and the supply voltage of the circuit.

are respectively the capacitance, the resistance and the supply voltage of the circuit.

- Since temperature and time stability of the characteristics of gas diodes and neon lamps is low, and also the statistical dispersion of breakdown voltages is high, the above formula can only give a qualitative indication of what the real frequency of oscillation is.

- Townsend avalanche discharges are exploited in devices such as Geiger counters and Proportional counters to detect and measure the energy of an ionizing radiation. Incoming radiation ionizes one of the atoms or molecules in the medium. When the electrons reach the anode, a current is induced, which is amplified further with electronics. This detects and measures some of the characteristics of the incident ionizing radiation.

See also

- Electric arc

- Avalanche breakdown

- Dark discharge

- Photoelectric effect

- Townsend (unit)

- Paschen's law

- Electric discharge in gases

References

- Little, P.F. (1956). "Secondary effects". In Flügge, Siegfried. Electron-emission • Gas discharges I. Handbuch der Physik (Encyclopedia of Physics). XXI. Berlin-Heidelberg-New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 574–663..

- James W Gewartowski and Hugh Alexander Watson (1965). Principles of Electron Tubes: Including Grid-controlled Tubes, Microwave Tubes and Gas Tubes. D. Van Nostrand Co, Inc..

- Herbert J. Reich (1939, 1944). Theory and applications of electron tubes. McGraw-Hill Co, Inc.. Chapter 11 "Electrical conduction in gases" and chapter 12 "Glow- and Arc-dischrage tubes and circuits".

- E.Kuffel, W.S. Zaengl, J.Kuffel (2004). High Voltage Engineering Fundamentals, Second edition. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3634-3.